A stillbirth is a baby born with no signs of life at or after 28 weeks gestation. In 2019, the stillbirth rate was estimated to be 13·9 stillbirths per 1000 total births globally. India was one of the three countries that contributed a third of these stillbirths [1]. Prolonged and obstructed labour, preeclampsia, and other maternal infections without adequate treatment account for the majority of stillbirths [2]. Stillbirths are largely preventable. High coverage of interventions before conception, as well as before, during, and after pregnancy, could prevent the occurrence of stillbirths. Over 40% of all stillbirths occur during labor, and this is a loss that could be avoided with timely access to emergency obstetric care [3]. Poor utilization of antenatal care also increases the chances of having a stillbirth [2,4], In 2014, the Every New-born Action Plan launched at the World Health Assembly set a target for national stillbirth rates (SBRs) of 12 or fewer stillbirths per 1000 births in all countries by 2030. In response, the Indian government launched the New-born Action Plan to attain the goal of ‘Single Digit SBR’ by 2030 [3,5], Achieving this goal would require targeted action in high-priority regions to reduce preventable stillbirths.

The Health Management Information System (HMIS) is the only source that monitors critical health indicators below the state level on a monthly basis. There is a need to examine the prevalence of stillbirths in the state and identify high-burden clusters (hotspots) that need prioritized action in the state.

Prevalence of stillbirths in Maharashtra

The overall rate of stillbirth (SBR) in Maharashtra, based on the HMIS dataset, was found to be about 9.04 per 1000 total births during the period of 2017-2020. The SBR per 1000 total births in rural Maharashtra during this period was higher (9.10) compared to urban Maharashtra (8.7). These stillbirth rates are relatively lower than the SBR of 12.9 per 1000 total births reported at all India levels during the same period. The state has observed some reduction in SBR. In 2017-18 and 2018-19, the stillbirth rates were 9.5 per 1000 total births in the state, which has reduced to 8.1 in 2019-20.

Source: HMIS

Note: For 2019-20, HMIS reported SBR together for Mumbai and Mumbai Suburban districts

Hotspots for stillbirth burden

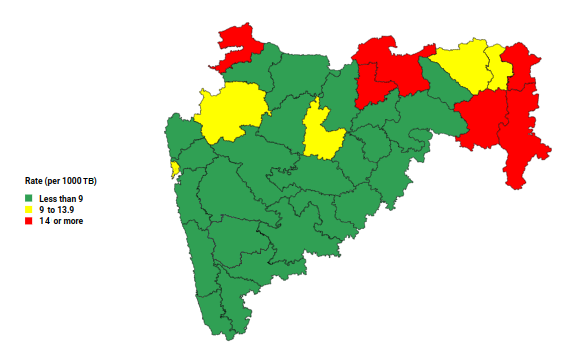

While Maharashtra reported moderate rates of stillbirth, the rates would further reduce if there is a focus on reducing preventable stillbirths in the districts that report the highest burden. The data shows that SBR was largely consistent during the period of FY 2017-18 to 2019-20. In all three consecutive financial years, the highest SBR was observed in the same six districts of Maharashtra—Gadchiroli, Chandrapur, Akola, Nandurbar, Amravati, and Gondia (Figure 1). In the high SBR burden districts of Gadchiroli and Nandurbar, the reduction in stillbirth rates was marginal between FY 2017-18 and 2019-2020. This lag in progress translates into many preventable stillbirths.

To examine significant hotspots (high-burden clusters) or cold spots (low-burden clusters) of stillbirth prevalence in the state, univariate LISA analysis was conducted using HMIS data. The hotspots or the ‘high-high’ category are districts that have an above-average prevalence of SBR, with the neighbors also reporting an above-average SBR. Cold spots or the ‘low-low’ category indicate the reverse trend. The univariate analysis of SBR data showed Gondia and Gadchiroli as part of the high-burden cluster, whereas Hingoli and Latur were cold spots. The Moran’s I value for SBR was 0.26, indicating some clustering at the district level. Identifying the hotspots of high stillbirth prevalence indicates the need for state administration to design focused interventions in these high-priority regions.

Is there adequate uptake of facility services?

Stillbirths can occur either before the onset of labour (antepartum death) or during labour (intrapartum death) [3]. Pregnancy and delivery complications, including anemia, eclampsia and other hypertensive disorders, preterm labour, placental abruption or haemorrhage, abnormal fetal position, breech presentation and obstructed labour significantly increase chances of stillbirth [5].

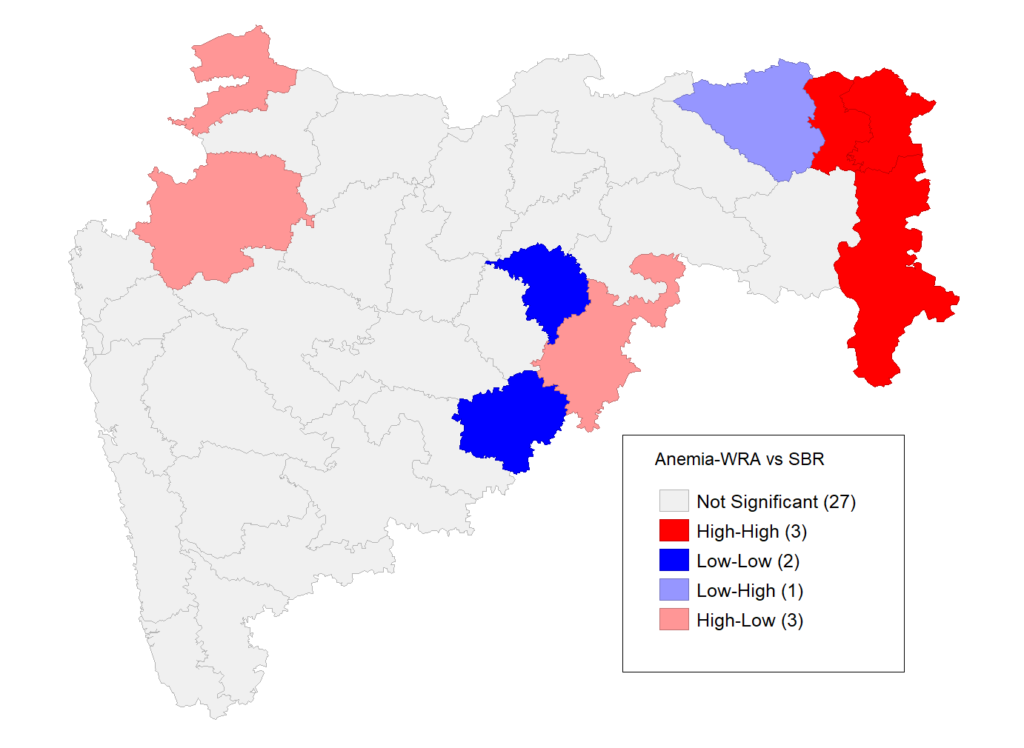

Similar to univariate, the bivariate LISA was conducted using HMIS and NFHS 5 data to further examine if there is a significant positive spatial autocorrelation between SBR and anaemia among all women in the reproductive age (WRA) which include pregnant women in the state.

Source: HMIS; NFHS -5

As seen in Figure 2, the districts that reported the highest SBR burden in Maharashtra also had a high prevalence of maternal anaemia (Moran’s I = 0.28). It is evident that pregnant women in the high burden districts are more likely to report maternal complications during their pregnancy term and would be in need of quality health services.

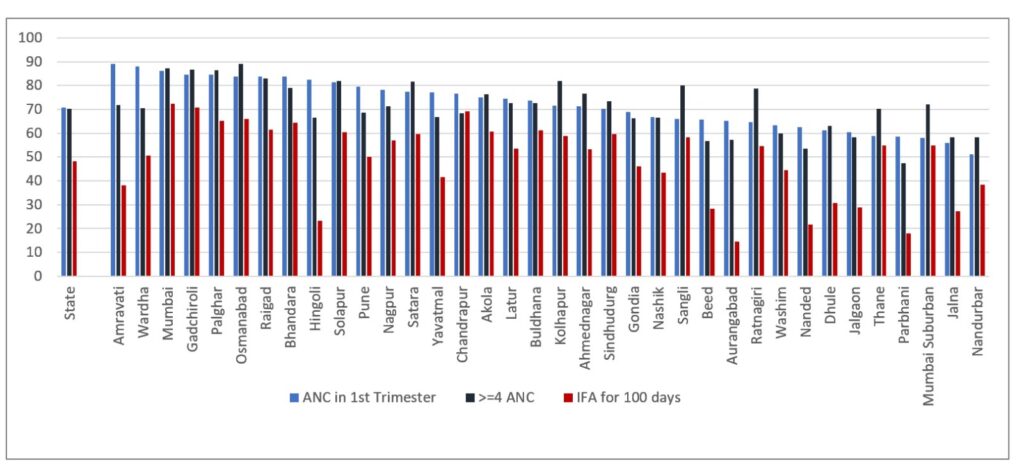

Evidence suggests that stillbirths are preventable through a wider reach of good-quality antenatal and obstetric care. The high incidence of stillbirths is also seen as a reflection of the status of antenatal and obstetric care services available in a given region. Studies have observed that increasing utilization of health facility services such as antenatal care (ANC) visits, IFA consumption, and institutional deliveries, including emergency care, helps reduce the risk of stillbirths [4,5,6]. Hence, it is important to review the status of key maternal health services in the districts.

As per NFHS-5, the coverage of IFA consumption for at least 100 days among pregnant women is low in 3 of the 6 districts with the highest SBR. Despite an ANC visit in the first trimester, several pregnant women have not received 4 or more visits during the entire pregnancy term. This gap is prominent for districts like Amravati that have reported a high SBR. Nandurbar is a district with poor performance in all the 3 ANC parameters (Figure 3). As per NFHS-5, Nandurbar also has the lowest rates of institutional deliveries in the state (76.3%), whereas the other 5 districts with the highest SBR have reported high rates of institutional deliveries (91.3% – 99.6%). However, Amravati, Akola, and Gondia districts also have high rates of caesarean deliveries (>25%).

Source: NFHS -5

However, where there is reach, substandard obstetric care can contribute to stillbirths. Studies have shown that most mothers whose pregnancies have ended in stillbirths have experienced one of the three delays: delay in seeking appropriate care, delay in reaching the health facility or delay in receiving appropriate care at a health facility [7]. A study in India particularly observed that reaching a facility within 30 minutes, timely management within 10 minutes of reaching the facility and timely management of complications during labour could have prevented 17%, 37%, and 20% of stillbirths [6].

Policy Implications

The identification of districts with the highest stillbirth burden highlights the need for prioritized action by the local administration. One concern was that high SBR districts, which reported high maternal anaemia prevalence also showcased poor rates of antenatal care service utilization. Some of the districts with the highest SBR in the state also have a notable population of Schedule Tribes [8].

For the purpose of evidence-based decision-making, it maybe important to also document the type of stillbirths (macerated or fresh) in these districts as it would indicate the type of action to be emphasized [7].

It must be noted that some districts with the highest SBR (Gadchiroli and Nandurbar) are also aspirational districts which also implies focus and monitoring of critical health and nutrition parameters in these districts. Similar to undernutrition, SBR can also be added as an important health outcome parameter for periodic monitoring in these districts.

Key takeaways & Policy Recommendations

Stillbirths are adverse pregnancy outcomes, most of which can be averted by a proactive health system through high coverage of obstetric services and adherence to appropriate practices. Analysis of HMIS and NFHS-5 data shows that districts with the highest SBR in the state also have high rates of anaemia among women in reproductive age. Regular third-trimester screening for foetal growth, screening of anaemia, iron, and folic acid supplementation, and institutional deliveries are some basic interventions that would potentially reduce rates of SBR.

Birth preparedness and early identification of high-risk pregnancies is critical. The district training centres under the Health Department need to emphasise these topics in their training module used for induction and refresher training of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). Pregnant women and their households have to be counselled by ASHAs to recognize pregnancy danger signs, risks of stillbirths, ensure maternal diet & well-being and that pregnant women undertake atleast 4 antenatal care visits.

Adequate compliance with referral policies to avoid unnecessary delays in deliveries is also important. District administration should also monitor the availability of transport services at primary health centre level to improve coverage of institutional births. In addition, improving the coverage of incentives for institutional deliveries for both mothers and community health workers.

References

- Hug, L., You, D., Blencowe, H., Mishra, A., Wang, Z., Fix, M. J., … & for Child, U. I. A. G. (2021). Global, regional, and national estimates and trends in stillbirths from 2000 to 2019: a systematic assessment. The Lancet, 398(10302), 772-785.

- Berhie, K. A., & Gebresilassie, H. G. (2016). Logistic regression analysis on the determinants of stillbirth in Ethiopia. Maternal health, neonatology and perinatology, 2(1), 1-10.

- WHO.(n.d.). Stillbirth rate (per 1000 total births). World Health Organisation (WHO). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/2444

- Goudar, S. S., Goco, N., Somannavar, M. S., Vernekar, S. S., Mallapur, A. A., Moore, J. L., … & Goldenberg, R. L. (2015). Institutional deliveries and perinatal and neonatal mortality in Southern and Central India. Reproductive health, 12(2), 1-9.

- Purbey, A., Nambiar, A., Choudhury, D. R., Vennam, T., Balani, K., & Agnihotri, S. B. (2023). Stillbirth rates and its spatial patterns in India: An exploration of HMIS data. The Lancet Regional Health-Southeast Asia, 9, 100116.

- Neogi, S. B., Sharma, J., Negandhi, P., Chauhan, M., Reddy, S., & Sethy, G. (2018). Risk factors for stillbirths: how much can a responsive health system prevent?. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 18(1), 1-10.

- Musafili, A., Persson, L. Å., Baribwira, C., Påfs, J., Mulindwa, P. A., & Essén, B. (2017). Case review of perinatal deaths at hospitals in Kigali, Rwanda: perinatal audit with application of a three-delays analysis. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 17(1), 1-13

- Government of India. (2011). Maharashtra district wise map-ST percentage. Census 2011. Retrieved from https://www.censusgis.org/india/

We acknowledge the support of the National Health Mission, CTARA-IIT Bombay, and the GISE Hub, IIT Bombay.

Authors

Marian Abraham, Prof. Sarthak Gaurav, Animesh Nautiyal

Marian Abraham is a Senior Research Analyst at the Koita Centre For Digital Health, IIT Bombay.

Prof. Sarthak Gaurav is an Associate Professor at Shailesh J. Mehta School of Management, IIT Bombay.

Animesh Nautiyal is a Project Research Assistant at Shailesh J. Mehta School of Management, IIT Bombay.